Therapies

Therapies for pancreatic disorders

Conservative Therapies for pancreatic disorders

The treatment of pancreatic disorders requires precise analysis. Conservative therapies can only be used, if the nature of the disorder is known, if pancreas cancer can be excluded or the tumour is inoperable. These therapies are an important post-operative tool.

Nutrition also plays a crucial role. Sufferers of pancreatic disorders should eat at least 6 times a day. This applies regardless of the exact nature of the pancreatic disorder except for acute phases of the disease or immediately after surgery, where special measures would be taken.

It is important that enough calories be fed to the body. Often, the weight loss we associate with the disease can be explained by the patient's insufficient food intake. Intake of fats is usually the problem, as they normally represent the main calorie providers and pancreas sufferers cannot easily absorb nutritional fats. An easily digestible fat is required and intake must be increased on a very gentle gradient. Middle-chained triglyerides (MCT-fats) such as margarine or oil can be consumed as additional energy source. These substances are beneficial, as they do not need to be broken down by digestive enzymes. Every pancreas sufferer should consult a nutritionist.

Exocrine loss of function of the pancreas

Repeated acute phases of the disease can reduce healthy pancreatic tissue to such an extent that digestive enzymes can no longer be produced in sufficient quantity to digest food. Undigested food particles remain in the intestines and cause bloating and diarrhoea, which will inhibit resorption (assimilation through intestines). This deficiency can be addressed with insulin replacement, using a processed and cleaned enzyme substitute produced from animal organs. However, some important factors must be considered: Enzymes must be taken with meals to be merged with the food. The quantity of stomach acid produced needs to be limited with acid inhibiting medication if the patient's stomach is fully intact. Normally, stomach acid is neutralised by the bicarbonate produced in the pancreas, but if the pancreas is not able to neutralise acid, food will remain sour in the intestines. Enzymes are not very effective under such conditions, even when taken as capsules. Some drugs are better than others. Declared enzyme quantities may be released too early or too late so that they will not be effective when needed in the intestines. If diarrhoea persists, the type of medication should be changed. A generous dosage should be taken, and only once food resorption is satisfactory, can the dosage be wound back.

As fat resorption is not always reliable, the metabolising of fat-soluble vitamins can be disrupted (these, by definition, need fat to be absorbed by the body). A blood test can ascertain the level of these vitamins (A, D, E, K) in the blood and an injection into muscle tissue will correct deficiencies found in the test. The intake of vitamins in tablet form is only advisable if the patient's resorption is effective. With these measures, deficiencies can be addressed before potential new disorders take hold. Bone damage such as osteoporosis and osteomalacia as well as vision impairment and skin damage are potential consequences, if vitamin deficiencies remain untreated.

Endocrine loss of function of the pancreas

Surgery and inflammation can reduce the number of insulin producing cells to such a degree that diabetes mellitus will develop. In many cases this disease also heralds the early development of pancreatic cancer. Diabetes patients suffer from a genuine insulin deficiency and treating the condition with tablet medication will only be successful in the short-term, if at all. It is important that diabetes sufferers have several smaller meals.

The deficiency in insulin producing cells during post-surgical treatment is of great significance, as the production of the insulin counterpart glucagon will also be non-existent, due to the lack of the same cell tissue. If patients inject themselves with insulin and, for whatever reason, miss out on food, they run the risk of acute blood sugar deficiency (the protective reaction of the body, which normally injects glucagon into the bloodstream when this occurs, is disabled due to the lack of pancreatic tissue). Blood sugar levels of patients without pancreas will therefore be kept somewhat higher, especially if no diabetes-induced long-term damage can be observed.

Post-operative check-ups and patient self help

Patients who have undergone pancreas surgery or those who suffer from chronic pancreatitis should be monitored on a regular basis to detect possible changes in their condition early on. This would include patients with diabetes, metabolism disorders such as deficiencies due to a lack of metabolised nutrients and vitamins and patients with any other personal complaint. The individual patient's medical history and condition will determine how frequently and to what extent these assessments should be carried out.

A self-help group has been established in Germany to help patients deal with post-operative stress. Chapters of this association (knows as AdP) are scattered all across the country.

Look for similar organisations in your area where patients are helping each other out to overcome post-operative stress and share their experiences for mutual benefit.

What options are available to the surgeon when operating on the pancreas?

Pancreas surgery can be performed for a variety of reasons. The nature of the particular pancreatic disease and symptoms will suggest the surgical procedure. Surgeons will usually consult with the patient and explain their intentions. Sometimes however, a different assessment will be made during actual surgery and the procedure can therefore be modified if necessary. A tailor-made solution, adapted to the individual patient's case is possible.

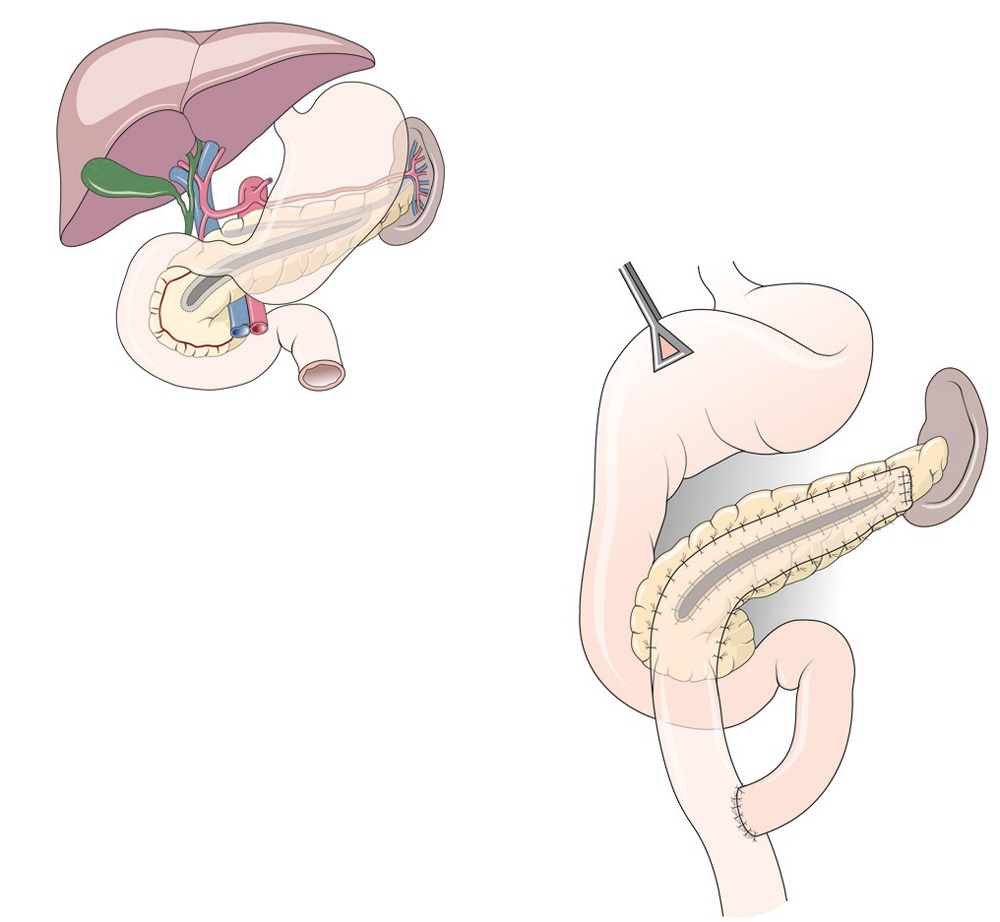

1. Surgical draining

This procedure will eliminate blocked pancreatic secretions caused by the disease. Most often the surgeon will operate on pseudo-cysts, found to have formed during pancreatitis. The surgeon will open up the cyst and connect it to an inactive loop of the small intestine. With this procedure, blocked secretions can be drained.

The entire pancreas may be opened, if the pancreatic duct becomes enlarged during chronic pancreatitis. The opened gland will then be sewn onto an inactive loop of the small intestine. This procedure will relieve pain, but can only temporarily correct misdirected secretion flows.

Food can no longer be passed on, if a tumour in the pancreas head blocks the duodenum. If the tumour cannot be removed totally, doctors will at least relieve pain and restore the patient's ability to eat normally. This procedure connects the stomach with the upper part of the small intestine, thus restoring food passage by bypassing the blocked duodenum, and it is known as gastroenterostomy.

Drainage-Operation. Secretions can flow in the small intestine.

Icterus (jaundice) will be found, if a tumour in the pancreas head prevents the flow of bile. Digestive malfunction and intense itching are often the consequences of the condition and joining the gall duct to the small intestine can bring relief. The procedure is known as biliodigestive anastomosis.

2. Resection surgery

Doctors must consider a variety of surgical procedures when dealing with pancreatic tumours or inflammation. Surgical and post-operative therapies are not always straightforward and will be tailor-made to the needs of the patient. One will always strive to preserve as much healthy tissue as possible. Maintaining a safe distance to the tumour when dealing with healthy tissue is crucial. Pathologists will determine that distance when they assess the affected tissue.

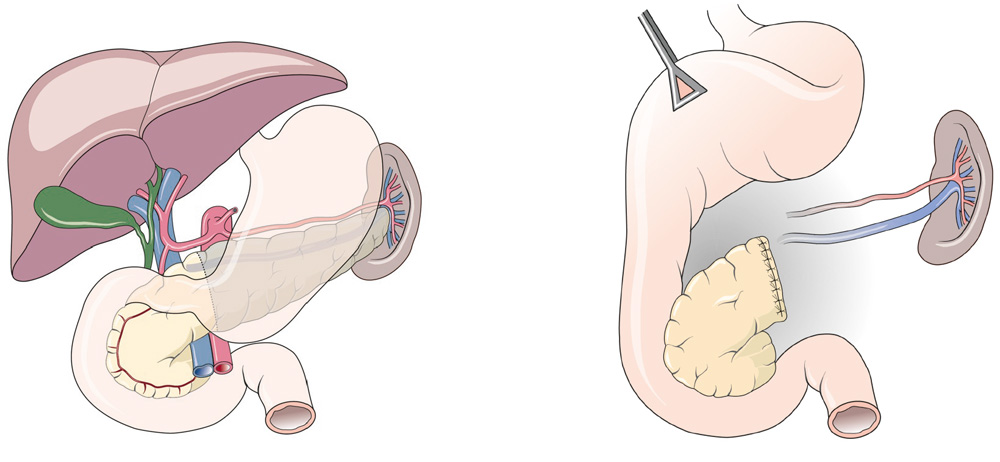

2.1 Left-Sided Pancreatic Resection

The surgeon will choose this procedure if tail or body of the pancreas is cancerous or inflamed. A part - variable as to size -of the gland is removed. Usually, the pancreatic duct is closed at the separation line, and in a considerable number of cases, surgeons will connect the pancreatic duct to an inactive loop of the small intestine. Every attempt will be made to leave the spleen intact, but this will sometimes be impossible, as blood supply of pancreas tail and spleen often are connected. The surgeon will usually prevent later complications be removing the gall bladder as well.

Post-surgical condition of the patient will depend on how much of the pancreas remains. In many cases, digestive malfunctioning or diabetes mellitus can be avoided. A more pronounced tendency to thrombosis, due to a higher number of thrombocytes, can emerge if the spleen was removed, as the body's patterns to fight infection will change.

Here the left part of the pancreas is removed (the spleen is also removed in the case of malignant tumors). A connection to a switched off small bowel loop may be necessary.

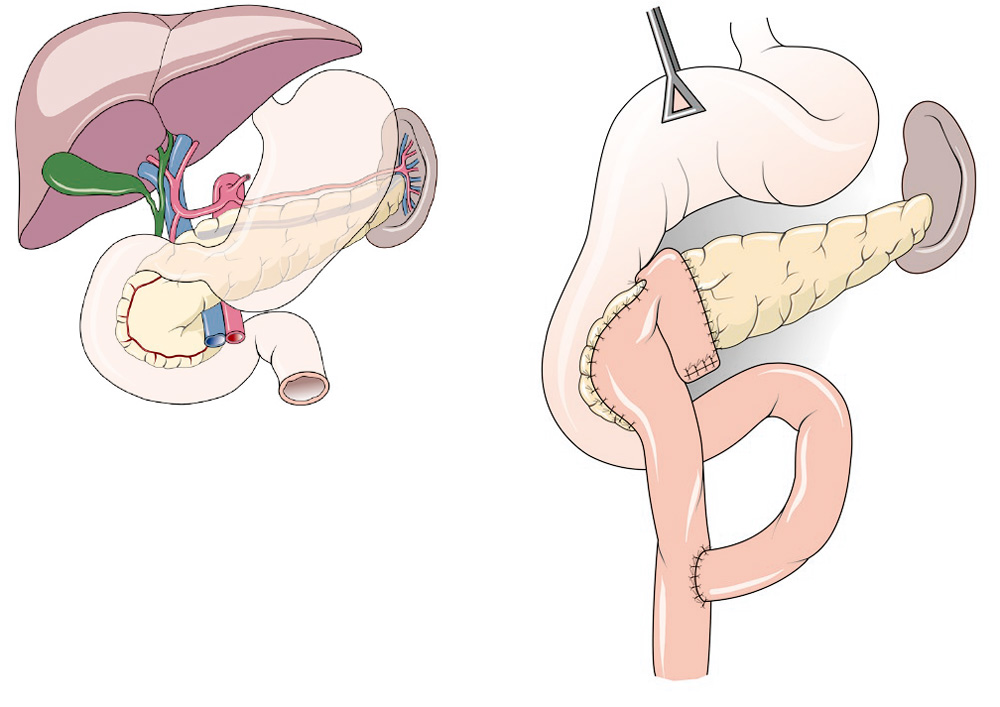

2.2 Duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection

This procedure will assist with the therapy of chronic pancreatitis. It will limit the loss of healthy tissue and therefore protect organs more effectively. Long-term damage is avoided while results are similar or better when compared to procedures used in the past.

The surgeon will sever connections between the pancreas head and the duodenum, a technically very difficult procedure. The bile duct must be left untouched to avoid any disruption of bile flow into the duodenum. The remainder of the pancreas is then sewn onto an inactive loop of the small intestine. This component of the procedure is particularly demanding, as aggressive pancreas secretions constantly affect the joined sections of pancreas, pancreatic duct and sewn-on small intestine.

The gall bladder is removed to prevent later complications with the flow of bile. Stomach and duodenum are not affected in the procedure. Remaining pancreatic secretions are merged in the upper section of the small intestines with food and bile. This ensures that the patient's digestive system will perform normally. It is sometimes necessary to sew the bile duct onto a loop of the small intestine. This will be done if the bile duct cannot be separated from inflamed pancreatic tissue (this is known as biliodigestive anastomosis). Success again depends on the degree to which pancreatic function has been reduced or lost. With lessening pain the patient will usually be able to eat normally. If this can be achieved, the doctor will be able to assess the patient's metabolism as to robustness and decide on an effective therapy (enzyme substitution, diabetic therapy, vitamin supplements).

A duodenum-preserving surgery can help stop the build-up of stalls and the ongoing inflammation. Here a separate loop is brought up to the removed tissue of the pancreatic head and sewn to the remaining part of the pancreatic head and the rest of the pancreas. The food is later introduced into the loop through the intestine.

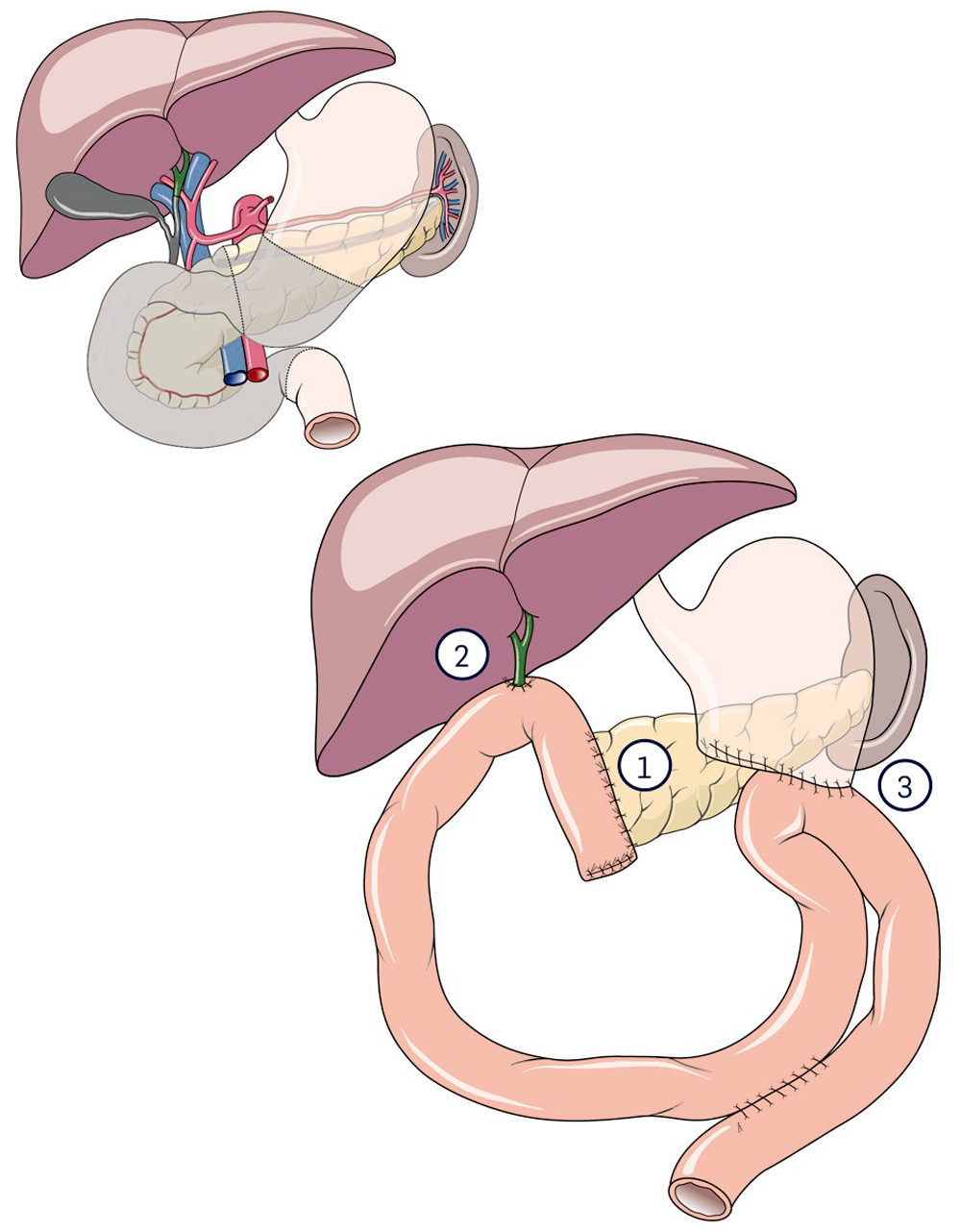

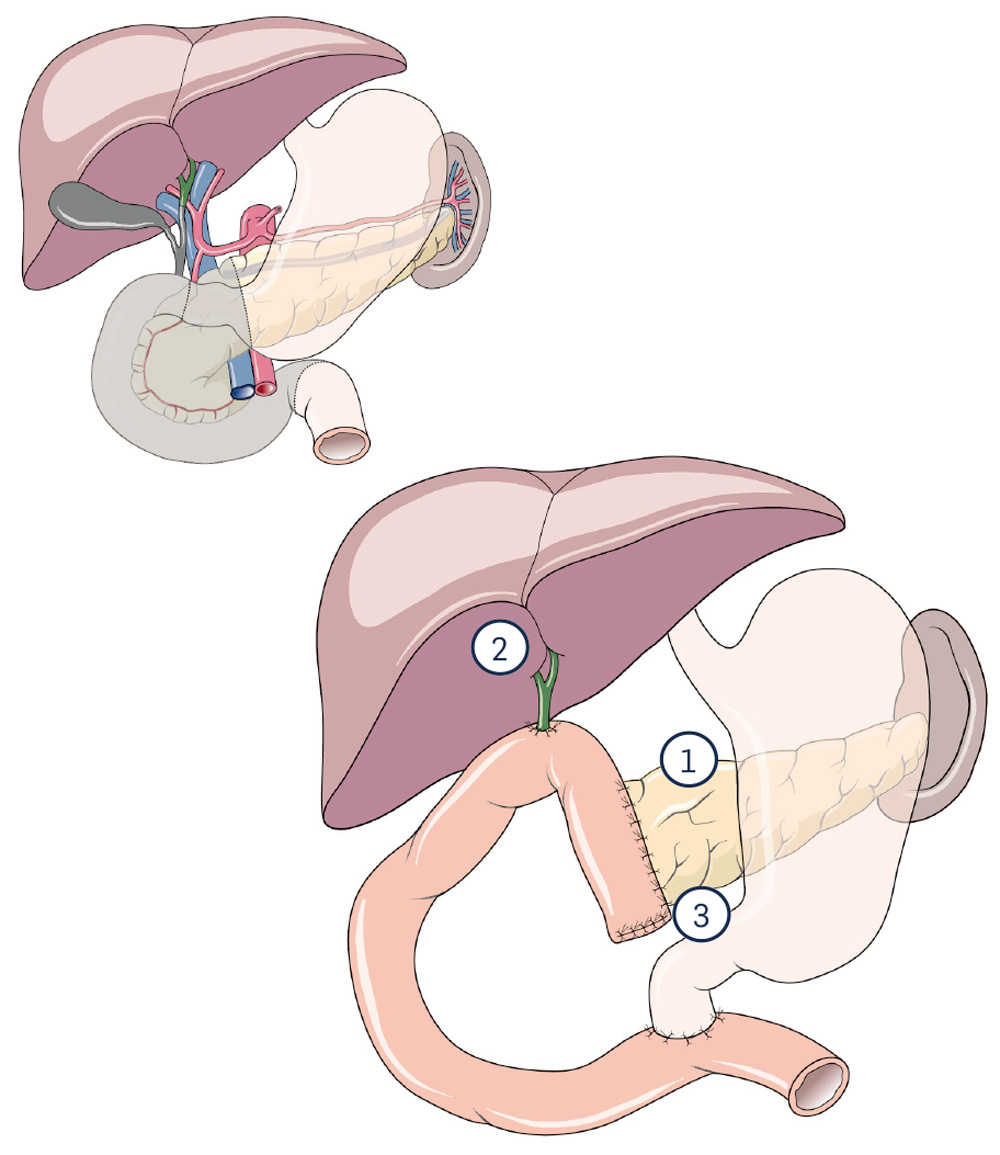

2.3 Pancreas Head Resection (Kausch/Whipple procedure)

This procedure has been performed since the beginning of last century. From the 1950s, with improved anaesthetic technology as a backdrop, the procedure became the standard therapy for cancer of the pancreas head. Today, we still use the same method, however a host of variations has evolved in the meantime.

The classic Whipple method involves the removal of 2/3 of the stomach, gall bladder, pancreas head and duodenum. Thus the surgeon can access the important lymph vessels, known as lymph nodes. For safety reasons these must be removed and assessed by the pathologist. It is here that the first small metastases, escapees of the pancreatic tumour will be found.

It is difficult to connect the remainder of the pancreas to a non-active loop of the small intestine, because aggressive pancreatic secretions will affect seams produced during the anastomosis between intestine, pancreatic duct and pancreas tissue. The bile ducts needs to be sewn onto a deactivated loop of the small intestine as well, since the duodenum has been removed.

If part of the lower stomach has to be removed, the operation is called "classic Whipple", although the German professor Walter Kausch established this operation in Berlin at the beginning of the 20th century.

1 Pancreatic anastomosis

2 Bile duct anastomosis

3 Aanastomosis of the stomach stump

These days, surgeons often use a variation of the Whipple procedure to preserve the stomach. Doctors refer to this procedure as the pylorus-preserving pancreas head resection according to Traverso (pylorus is the stomach gateway).

Diverse conditions can give rise to unwanted post-operatic fallout, when this procedure is applied. Loss of pancreatic functions with associated symptoms (lack of enzymes, diabetes mellitus and lack of vitamin absorption) depends on how much pancreatic tissue has been removed. Complications may also emerge, if the stomach was partly removed (dumping syndrome, lack of vitamin B12, incompatible bacteria in the small intestines etc).

Constriction of gall duct anastomosis with ensuing obstruction of gall flows or, as pointed out above, incompatible bacteria in the small intestines can lead to ascending inflammation of the gall duct. A narrowing of the anastomosis can lead to an obstruction in the food passage through the stomach outlet when using the abovementioned organ-preserving procedure.

In contrast to the classic Whipple, the stomach can be completely preserved (so-called pylorus-preserving variant). The restoration is simplified by the complete preservation of the stomach.

1 Pancreatic anastomosis

2 Bile duct anastomosis

3 Anastomosis of the duodenal stump

(Anastomosis = connection)

2.4 Pancreatic head preserving duodenal resection

This recently developed procedure allows the surgeon to preserve the pancreas head when cancer is found in the papil (combined gall and pancreas secretion duct), by removing only the duodenum. Complicated sewing techniques must be used, as pancreas duct, bile duct and stomach must be attached to the small intestine, however the surgeon will be able to preserve the organs. The Whipple procedure would have previously been unavoidable in this case.

Negative results can only arise through faulty anastomosis. No long-term statistical results are yet available for this recently developed procedure.

2.5 Total Pancreatectomy

This procedure involves disposing of the entire gland. 2/3 of spleen, stomach, duodenum and gall bladder are removed along with the pancreas. Technically speaking, pancreatectomy is easier to perform than the classic Whipple procedure, as no anastomosis needs to be applied. As with other procedures, the smaller-size stomach needs to be connected with the small intestine. However unwanted outcomes can be considerably more serious. The operation is therefore only used as a last resort, when it is not possible to preserve pancreatic tissue by any means. In any case, the bile duct must be connected to an inactive loop of the small intestine. Many variants of the procedure exist these days, e.g. surgeons will attempt to preserve stomach and/or spleen.

The main issue with this procedure is the patient's metabolism. This type of diabetes is difficult to control as both insulin and its counterpart, glucagon are no longer produced. As a result the patient is exposed to a high risk of hypoglycaemia (lack of blood sugar). Similar unwanted complications (cf. Whipple procedure) can also emerge here, but they are of a more serious nature, as diabetes sufferers must keep up a constant intake of food to avoid a drop in blood sugar levels.

Removal of the spleen weakens the patient's infection resistance and often causes a substantial increase in the number of thrombocytes (blood platelets). Thus, an elevated risk of thrombosis is unavoidable (that risk is at any rate considerable in cancer patients).

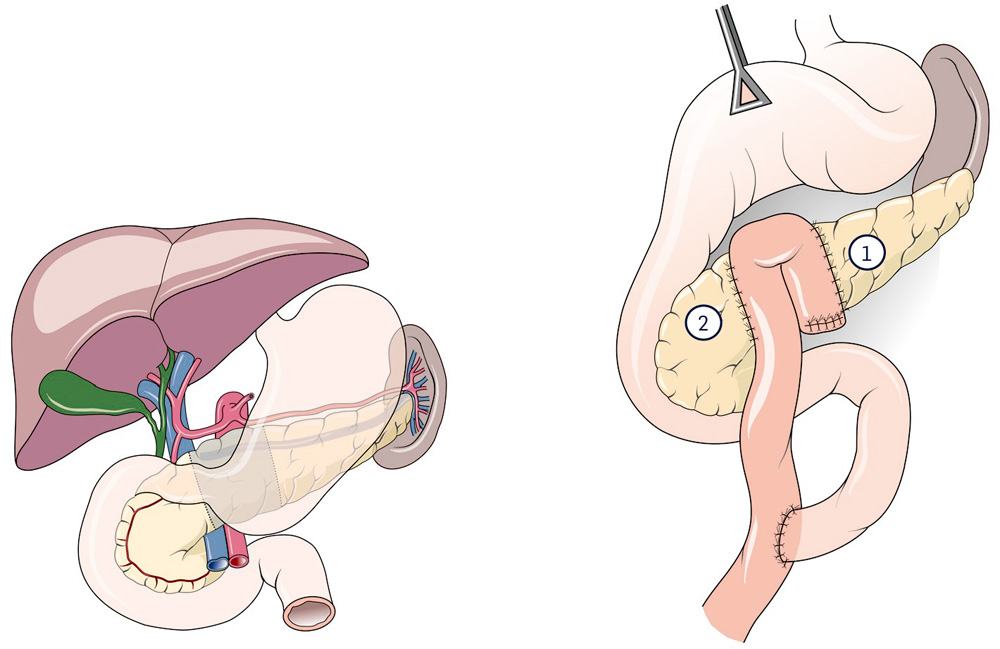

2.6 Segmental resection of the pancreas

Sometimes it is possible to remove a small tumour in the body of the pancreas without damaging or removing other organs. Thus, a pancreas head with duodenum and a pancreas tail with spleen can be preserved. To connect the remaining parts of the pancreas with the intestines can be difficult in this procedure. Either the pancreas head is sealed at the end and pancreatic fluid (insulin) will then flow into the duodenum, or the surgeon will connect a loop of the small intestine with pancreatic duct and tissue. This loop must also collect pancreatic secretions emanating from the pancreas tail. Insulin or pancreatic enzyme deficiencies are usually not the cause of a negative outcome. It is more likely that the degree of technical difficulty encountered in this procedure will generate problems. Hence, the operation should only be performed in specialised clinics.

With benign (rare) tumors in the area of the pancreas body, an organ-preserving operation (segment removal) can occasionally be carried out. It is named after its first descriptor (Prof. Andrew Warshaw). The procedure is rarely carried out.

New connections are made to the pancreatic tail and head.

1 Pancreatic anastomosis left-sided

2 Pancreatic anastomosis head-sided

to top